BACK TO HELL. 2013

Kids take a photo near Vukovar on a tank that defense the city in 1991.

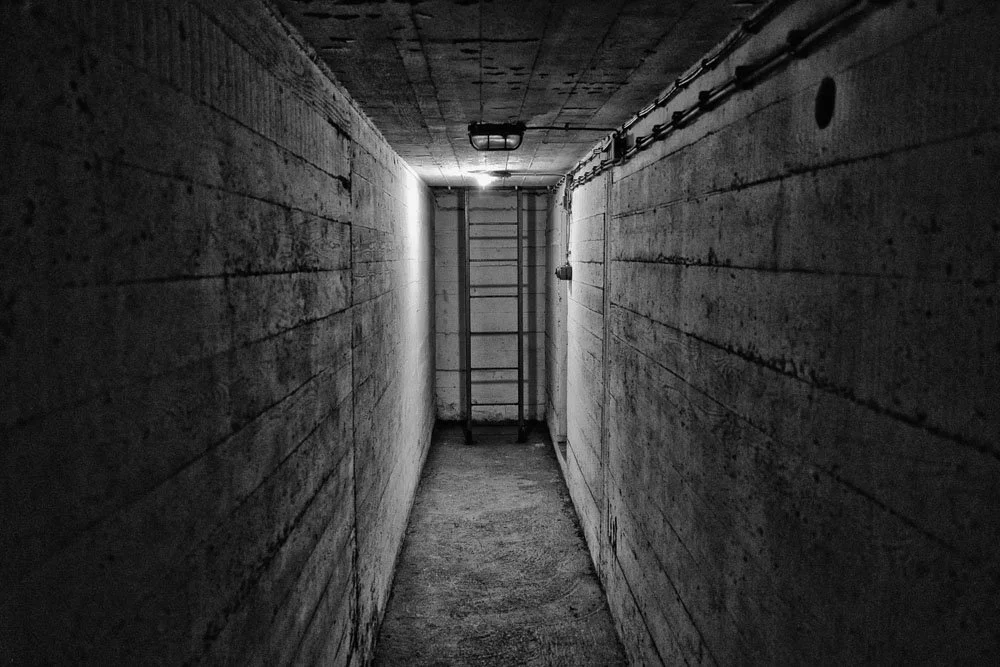

Should I back to hell after many years?

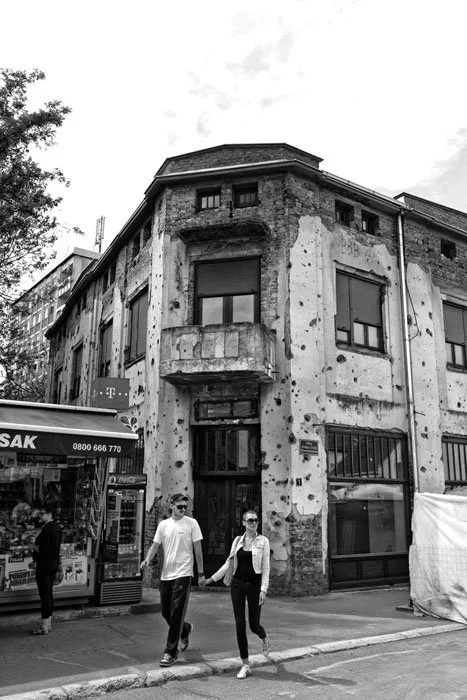

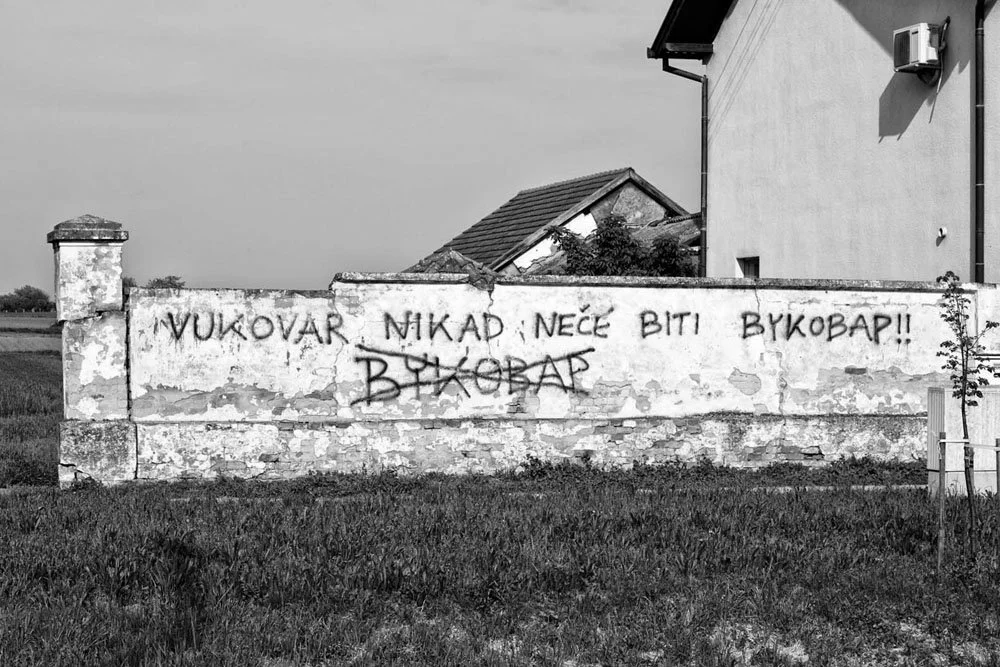

The Vukovar .water tower (Croatian: Vukovarski vodotoranj) is a water tower in the Croatian city of Vukovar. It is one of the most famous symbols of Vukovar and the suffering of the city in the Battle of Vukovar and the Croatian War of Independence, when the water tower and the city itself were largely destroyed by Yugoslav forces.

The photo of the girls being photographed on a tank used in the defense of the siege of Vukovar is probably the one that gave me the most peace when I returned to what we knew as hell.

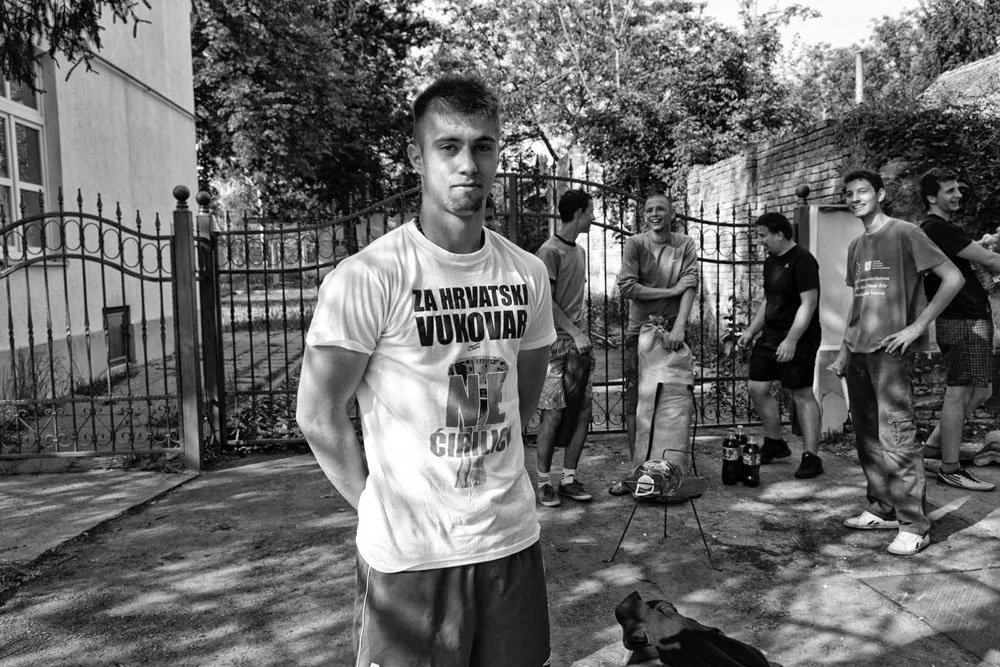

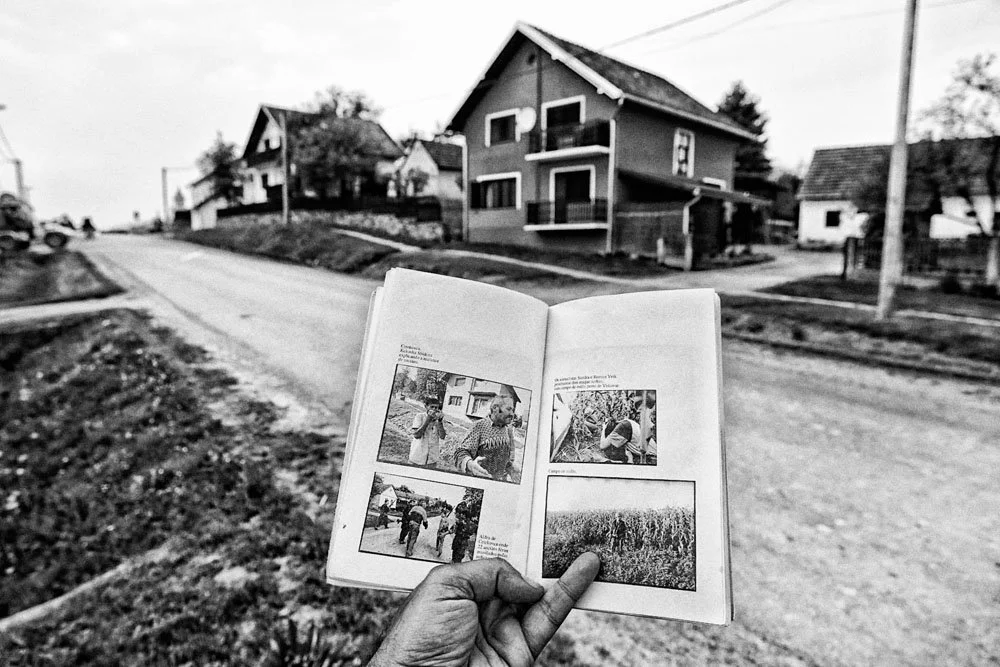

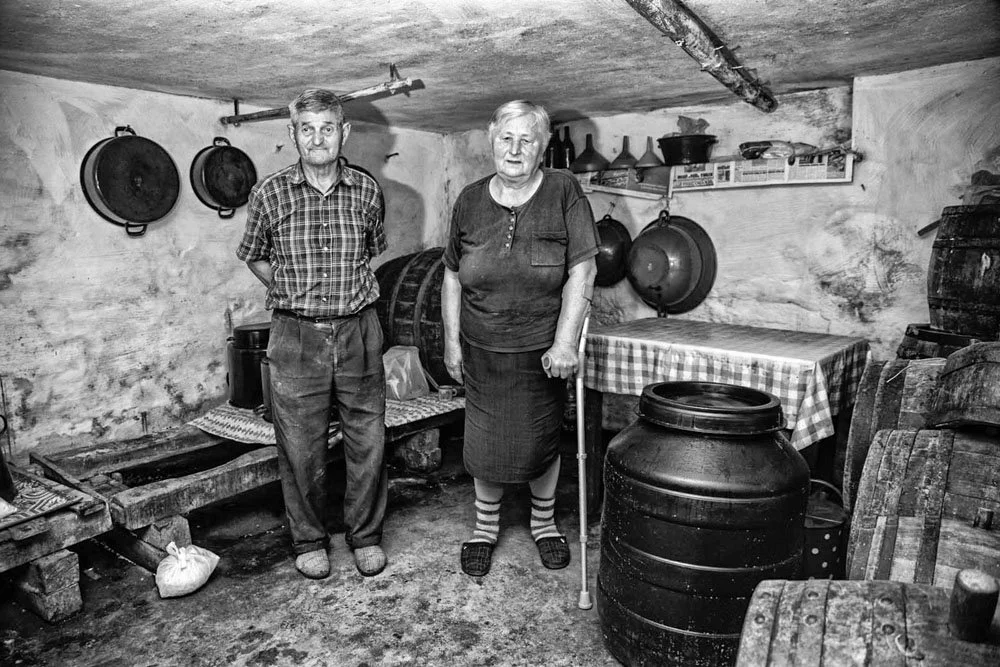

For many years, I wanted to return to Vukovar, to walk around and remember the moments with the people I had fought with while fighting for their families.

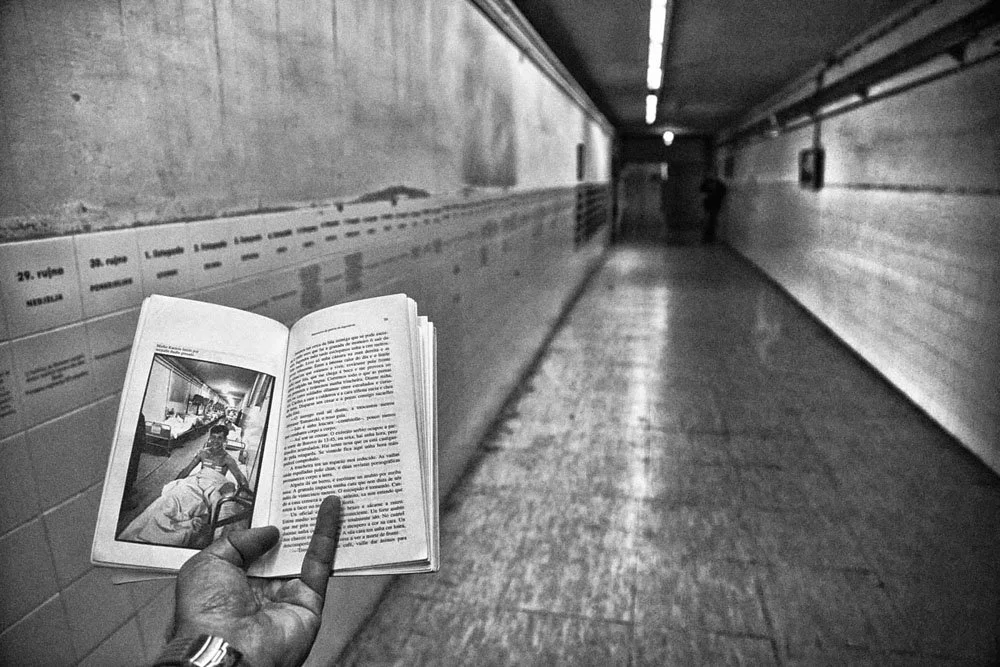

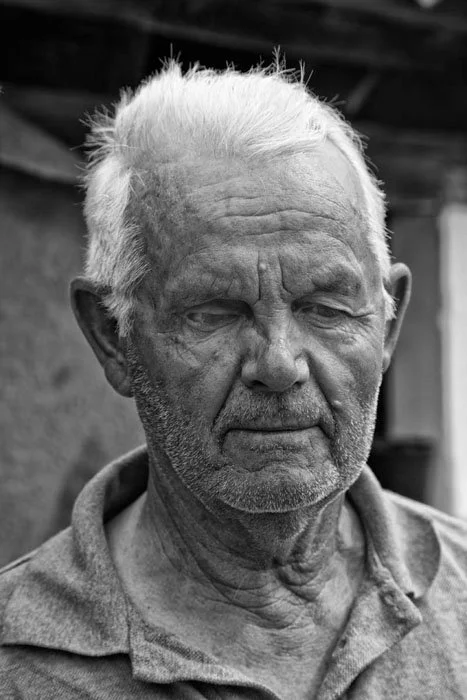

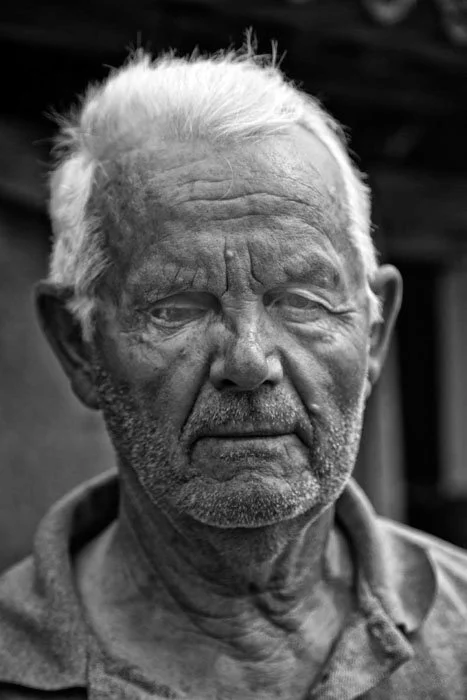

Many of those men are no longer alive, and I always remembered one: Marko Karaula, a boy who made me see the war through his eyes, escaping through cornfields at the end of a summer in 1991, the worst of my life and that of thousands of others.

I wanted to go back many times; it was so simple. Plane tickets were cheap, renting a car at the airport, driving for hours on end, in the humid heat and mosquitoes that the front grille of the car kept catching like an insect-collecting machine. I didn't have enough courage to make a decision, then my three daughters came into the world, and just thinking about having to return to the fucking hell of Vukovar was traumatic, perhaps my own cowardice in facing the times I'd lived through.

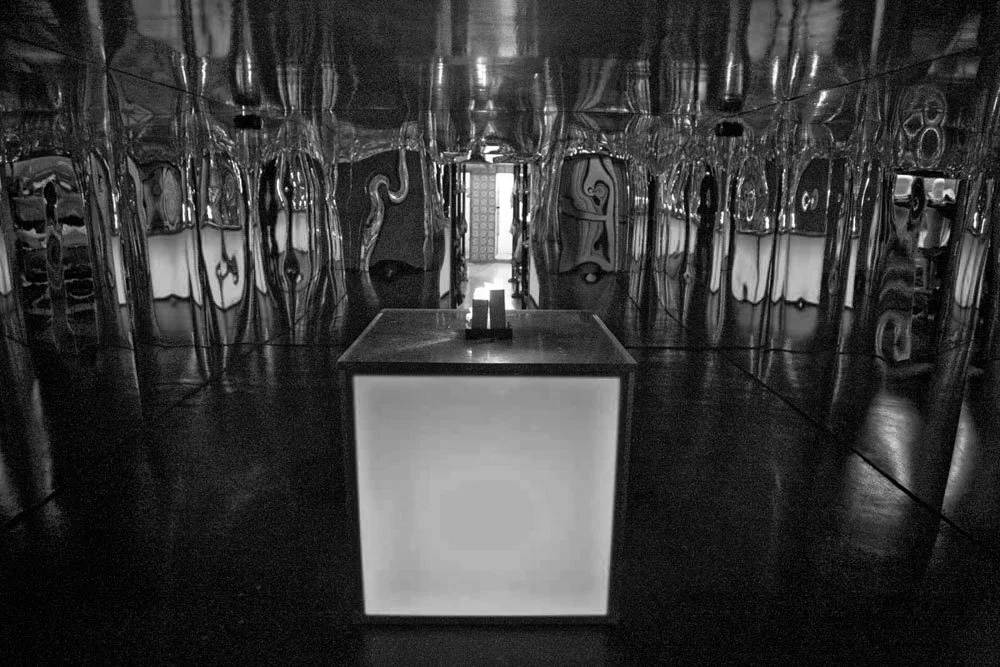

Today, June 2025, I managed to find a moment, some inspiration, to upload some photos and write, because the important thing, according to a friend who works with people with PTSD, is to write and share, to learn to live with what you've experienced, constructively, at peace with yourself.

But I want to return to the photo of the girls and the tank. It's beautiful in its content. Possibly those girls who weren't even born in 1991 have relatives and friends who fought on the Vukovar front. I remember the first time I saw one of those heavy, iron-clad tanks in a cornfield. The smell of diesel was stinking, and its track was broken by an anti-tank mine. The platoon I rode with every day to the front, including Marko, had set a trap for it, and when they stepped on the grenade, the tank exploded. There were also more military vehicles around them. The tank's occupants jumped out and fled across the fields, through the cornfields. They were let go. No one shot at them. They ranning like hell, like hares chased by greyhounds, without looking back.

That tank, where the girls are, could have been the same one as the platoon of civilians turned soldiers, the same one from that summer morning, and I was staring at the scene. I looked for an angle so that only the tank and the girls were there, but the sun was setting too quickly, mosquitoes were piercing my legs like kamikazes in battle, and between so much thinking and searching for positions, I only managed to get this single image. I adore it. It gives me great strength, and today, as the father of two beautiful twin girls, I think of the many children who were killed during the war and those who continue to die in others, and then I get angry with myself, and I wouldn't go back to battle even if they gave me all the gold in the world.

Am I getting old? Yes, of course. Nothing is eternal. We must live in the present, because the future is only a dream that crosses our paths with ideas and projects. Some will come true, others will depend on fate and the life of each of us.

I remember that afternoon, a very old, yellow biplane flew very low, spraying pesticide against mosquitoes. The streets became a cloud with a chemical smell, and meanwhile, the sun slowly disappeared, leaving a reddish sunset, a hot afternoon, and a blue sky with hardly any clouds on the horizon.

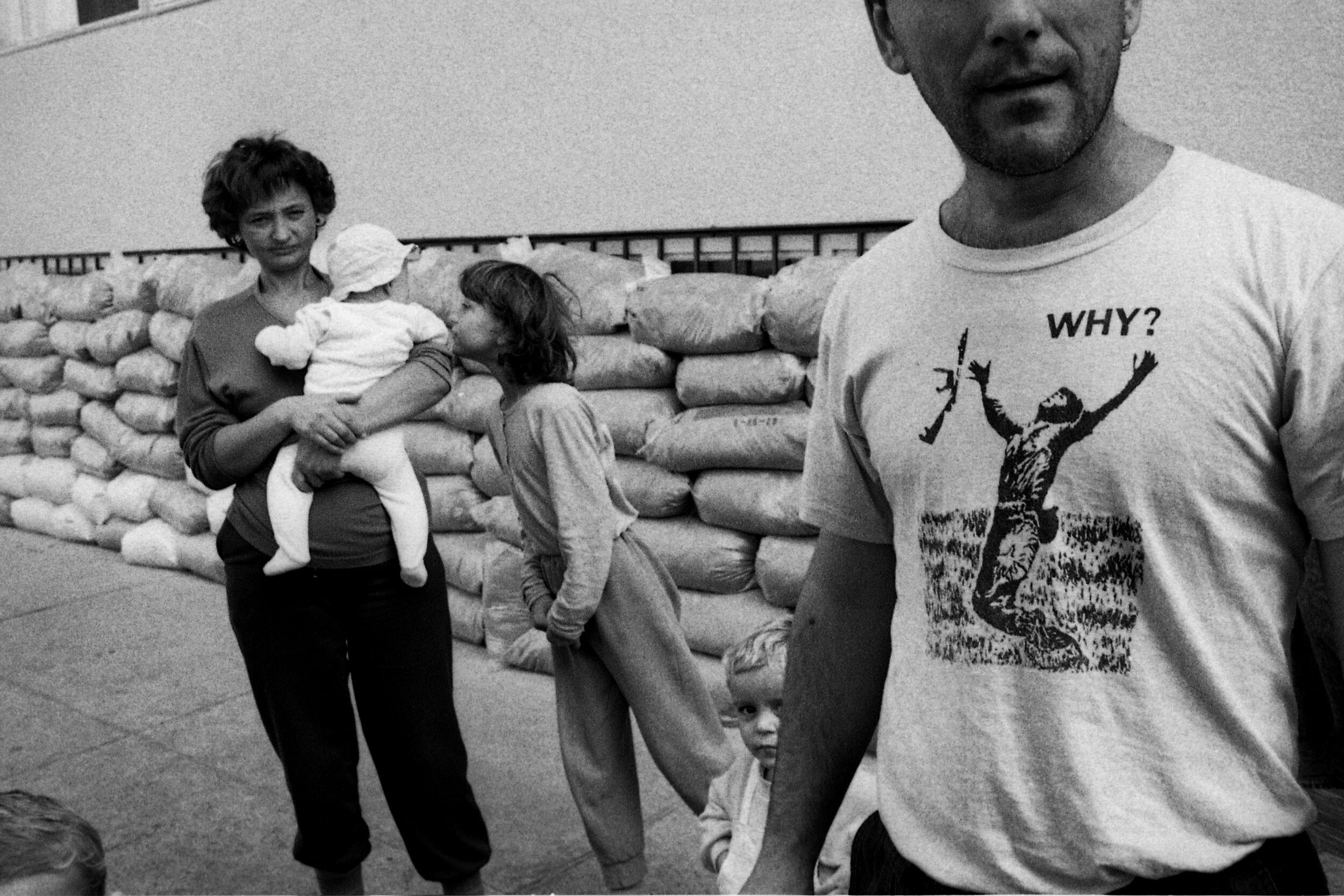

Yugoslavia war. 1991-93

The news broadcasts opened their headlines at lunchtime, in that hot summer of 1991, with an escalating war in Europe. Someone at the table asked for silence. The blurry color images showed tanks at a Slovenian airport and trains loaded with military equipment. In other scenes, people ran through deserted streets and took cover alongside soldiers and police trying to repel gunfire from building windows. The journalist himself described the chaotic situation, naming locations where armed clashes were presumably taking place. Access to these locations was complicated and difficult, with few images from independent media outlets to contrast the information that trickled in.

At the Moskva Hotel in Belgrade, CNN was reporting on the conflict, and the hotel receptionist frowned in a mood of indifference and confusion.

BACK TO HELL 2013F

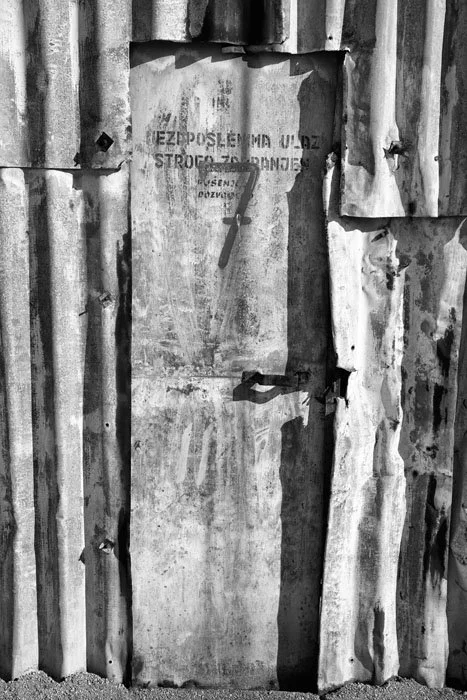

Finally I decided back to hell with a memory full of images, bodies, blood, children, women, men, corn fields, Imagining finding Vukovar destroyed and in ruins, despite the time that had passed. Those were the images I'd last seen of a place I'd never imagined returning to again. Wiktor drove the Volkswagen Polo at his own pace, which rarely dropped below 140 km/h. The windows were down in the unbearable heat, and at one point I fell asleep, so relaxed I was, but I woke up to the sound of a large insect hitting the car window, where a stain of blood and excrement had been left.

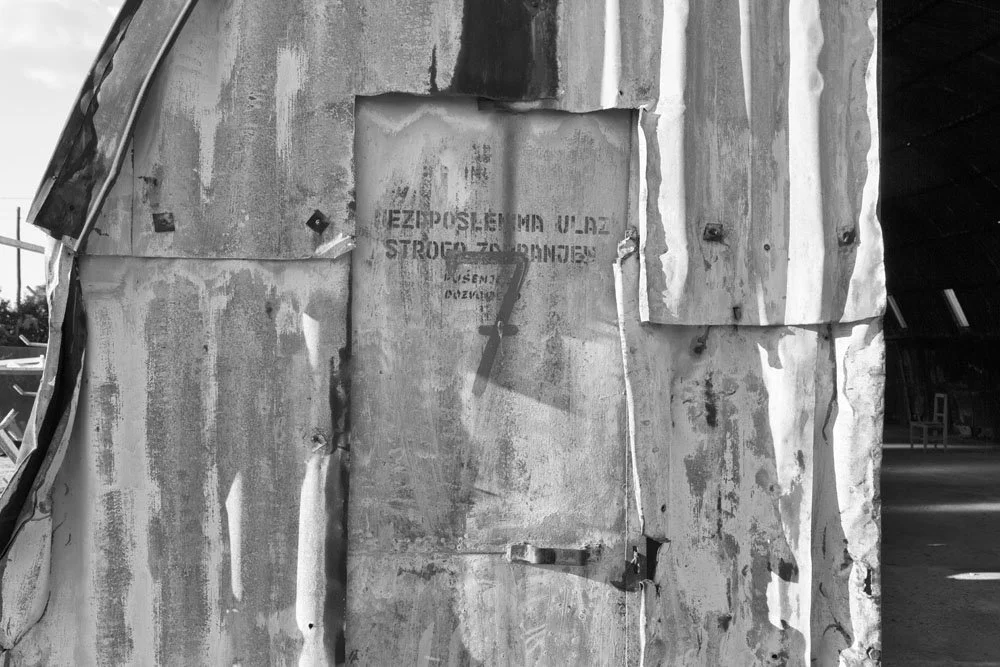

In the summer of 1991, it was unthinkable to travel on these roads, all blocked off and manned by military checkpoints. They became a no-man's-land, and the umbilical cord that crisscrossed Yugoslavia trapped thousands of people in their vehicles, not knowing which way to go.

This vital artery, so essential to life and the economy, had been reduced to nothing, where the masters and owners of both sides wielded force, robbery, violence, and ultimately death right there in a summary trial—a full-blown ethnic cleansing.